Construction accounting

/What is Construction Accounting?

Construction accounting is a form of project accounting in which costs are assigned to specific contracts. A separate job is set up in the accounting system for each construction project, and costs are assigned to the project by coding costs to the unique job number as the costs are incurred. These costs are primarily comprised of materials and labor, with additional charges for such items as consulting and architectural fees. A number of indirect costs are also charged to construction projects, including the costs of supervision, equipment rentals, support costs, and insurance. Administrative costs are not charged to a construction project unless this is allowed by the customer.

Related AccountingTools Courses

Auditing Construction Contractors

Types of Construction Contracts

There are several types of contracts than a contractor can enter into with a client. Each type has specific characteristics that tend to favor one party or the other, depending on the circumstances. We explain each one below.

Fixed Fee Contract

A fixed fee contract is used when the contractor commits to being paid a fixed amount by the client. In this situation, the costs incurred by the contractor have no impact on the price paid. This arrangement would appear to strongly favor the client, since there is no risk of paying more than the contract price. In fact, this arrangement is most common in a multi-party bidding scenario where a number of potential contractors are forced to bid against each other. It is best from the perspectives of both the client and contractor to create quite detailed specifications for a fixed fee contract, so there is little question about what is expected of the contractor and what constitutes an acceptable final outcome.

Cost Plus Contract

A cost plus contract is a cost-based method for setting the price of a construction project under a contractual arrangement. The contractor adds together the direct material cost, direct labor cost, and overhead costs for a project and adds to it a markup percentage in order to derive the price to be billed. From the client’s perspective, this can be an expensive pricing system, since costs may spiral well above initial expectations. However, it is an ideal system when there is a high degree of uncertainty regarding the design specifications of the final product.

Time-and-Materials Contract

A time-and-materials contract is a variation on the preceding cost plus contract. Customers are billed a standard hourly rate per hour worked, plus the actual cost of materials used. The standard labor rate per hour being billed does not necessarily relate to the underlying cost of the labor; instead, it may be based on the market rate for the services of someone having a certain skill set, or the cost of labor plus a designated profit percentage.

Unit-Price Contract

A unit-price contract is an arrangement in which the client pays a specific price for each unit of output. This arrangement is rarely used in a large, complex construction project where there are few units of output that are easily replicated. For example, a client is unlikely to demand a unit-price contract for each of a cluster of apartment buildings. However, the general contractor may use this type of contract with its subcontractors for selected work arrangements. For example, a general contractor for the construction of a road could enter into a unit-price contract that pays a certain amount per square foot of sidewalk installed.

Revenue Recognition

The revenue recognized under a contract may be based on the completed contract method when it is not possible to determine the percentage of completion of a project. As the name implies, this means that the contractor recognizes all of the project revenue and profit only when a project has been completed. More commonly, the percentage of completion method is used, under which the contractor recognizes revenue by applying the estimated percentage of completion to the total anticipated profit. This approach allows the contractor to recognize revenue and profits at regular intervals over the term of a project. Another option is the cash method, under which revenue is recognized only when cash is received; this approach works best for smaller, short-duration projects.

Percentage of Completion Method

The percentage of completion method involves the ongoing recognition of revenue and income related to longer-term projects. By doing so, the company can recognize some gain or loss related to a project in every accounting period in which the project continues to be active. For example, if a project is 20% complete, the company can recognize 20% of the expected revenue, expense, and profit. The method works best when it is reasonably possible to estimate the stages of project completion on an ongoing basis, or at least to estimate the remaining costs to complete a project.

Conversely, this method should not be used when there are significant uncertainties about the percentage of completion or the remaining costs to be incurred. The estimating abilities of the business should be considered sufficient to use the percentage of completion method if it can estimate the minimum total revenue and maximum total cost with sufficient confidence to justify a contract bid.

In essence, the percentage of completion method allows you to recognize as income that percentage of total income that matches the percentage of completion of a project. The percentage of completion may be measured in any of the ways noted below.

Cost-to-Cost Method

The cost-to-cost method is a comparison of the contract cost incurred to date to the total expected contract cost. The cost of items already purchased for a contract but which have not yet been installed should not be included in the determination of the percentage of completion of a project, unless they were specifically produced for the contract. Also, allocate the cost of equipment over the contract period, rather than up-front, unless title to the equipment is being transferred to the customer.

Efforts-Expended Method

The efforts-expended method is the proportion of effort expended to date in comparison to the total effort expected to be expended for the contract. For example, the percentage of completion might be based on labor hours expended to date.

Units of Work Performed Method

The units of work performed method is the proportion of physical units of production that have been completed to date. For example, the percentage of completion could be based on material quantities installed, such as square yards of concrete laid or cubic yards of material excavated to date. This approach does not work well when significant costs are incurred prior to or following the production of physical units. For example, laying a pipeline involves building an access road to the pipeline location; the cost of constructing the road would result in no earned revenues if the percentage of completion is based on the number of feet of pipe laid.

Completed Contract Method

Under the completed contract method, business recognizes all of the revenue and profit associated with a project only after the project has been completed. This method is used when there is uncertainty about the collection of funds due from a client under the terms of a contract. For example, it would be used for a speculative project where there is no buyer of a property.

This method yields the same results as the percentage of completion method, but only after a project has been completed. Since revenue and expense recognition only occurs at the end of a project, the timing of revenue recognition can be both delayed and highly irregular. Given these issues, the method should only be used under the following circumstances:

When it is not possible to derive dependable estimates about the percentage of completion of a project; or

When there are inherent hazards that may interfere with completion of a project; or

When contracts are of such a short-term nature that the results reported under the completed contract method and the percentage of completion method would not vary materially.

If a contract is being accounted for under this method, record billings issued and costs incurred on the balance sheet during all periods prior to the completion of the contract and then shift the entire amount of these billings and costs to the income statement upon completion of the underlying contract. A contract is assumed to be complete when the remaining costs and risks are insignificant.

If there is an expectation of a loss on a contract, record it at once even under the completed contract method; do not wait under the end of the contract period to do so.

Unpriced Change Orders

A construction company is dealing with an unpriced change order when the parties cannot initially agree on the price to be charged by the company to the client for a modification of the underlying construction contract. The recovery of funds from an unpriced change order is considered probable when the client has approved of the scope change in writing, and the contractor has documented the related costs of the change, and the contractor has a favorable history of settling change orders. There are three variations on how to deal with an unpriced change order. They are as follows:

When it is not probable that the costs associated with an unpriced change order will be paid back to the contractor through a price increase, the costs are added to the total estimated cost of the project; the result is a decline in the estimated amount of profit that the job will generate.

When it is probable that an upward adjustment to the contract price will be forthcoming, defer the recognition of any costs incurred under the change order until the price has been settled.

When it is probable that the prospective upward adjustment to the contract price will exceed the costs associated with the contract and the amount of the price can be reliably estimated, adjust the contract price to reflect the amount of the increase in costs. Do not recognize revenue exceeding the amount of costs incurred for the change order unless receipt of the estimated revenue amount is assured beyond a reasonable doubt.

When a change order is in dispute, it should be evaluated as a claim rather than a change order (as noted next).

Contract Claims

A construction company is not usually allowed to recognize any revenue associated with claims, given the risk that the client will not pay for them. Revenue recognition is only allowed when it is probable that additional revenue will result and that the amount of the additional revenue can be reliably estimated. For these criteria to be present, the following conditions must be satisfied:

The evidence upon which the claim is based is objective and verifiable

There is a legal basis for the claim or a legal opinion states that there is a legal basis for the claim

The additional costs were caused by unforeseen circumstances

The additional costs are not the result of the contractor’s poor performance

The costs linked to the claim are readily identifiable

The costs linked to the claim are reasonable, based on the contractor’s work

Even when all of the preceding conditions have been satisfied, the amount of revenue that can be recorded is limited to the contract costs associated with the claim.

Overbilling Liabilities

When the amount billed on a construction project exceeds the costs incurred to date, the excess represents a billing in advance of performance. Under the percentage-of-completion method, this situation reflects that the contractor has invoiced the client for work not yet performed, creating a temporary overstatement of revenue relative to the actual progress of the project. To ensure accurate financial reporting, this difference is recorded as a liability on the balance sheet, typically labeled “Billings in Excess of Costs and Estimated Earnings.” This liability indicates an obligation to perform future work or, in some cases, the potential need to refund unearned amounts. As the contractor incurs additional costs and progresses on the project, the liability is gradually reduced, aligning revenue recognition with actual performance. This treatment ensures compliance with the matching principle and prevents premature revenue recognition.

Contract Retainage

A customer may withhold a specified amount from the contract price until satisfied with the completed work. Doing so gives the customer some leverage over the contractor to complete the work in a satisfactory manner. These retainage amounts may still be recorded as receivables, but could be classified as long-term receivables if the customer has the right to hold these amounts for more than a year. In addition, the IRS allows a company to exclude retainages from the recognition of income until there is an unconditional right to receive them.

Construction Accounting Reports

There are several reports that can be used in construction accounting. They are noted below.

Job Cost Sheet

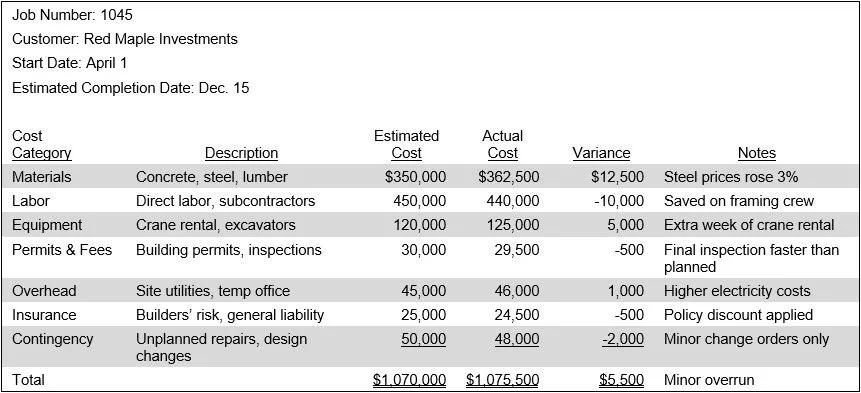

A job cost sheet is a compilation of the actual costs of a job. The report is compiled by the accounting department and distributed to the management team, to see if a job was correctly bid. The sheet is usually completed after a job has been closed, though it can be compiled on a concurrent basis. A job cost sheet can be quite complex to create, since it may involve different labor rates for dozens of people, as well as a labor allocation for the payroll taxes and benefits incurred by those people, and overtime, plus potentially hundreds of components that should include the cost of shipping and handling. Depending upon the format of the job cost sheet, it may also include subtotals of costs for materials, labor, and overhead. A sample job cost sheet appears in the following exhibit.

Construction-in-Progress Report

A construction-in-progress report provides a snapshot of the current status of a construction project. It lists the total project budget, funds used to date, and remaining funds, as well as the details on any approved or pending changes that impact costs. The report also notes discrepancies between projected and actual expenses. In addition to these financial issues, the report also notes which tasks have been completed, highlights current work activities, and provides an overview of upcoming tasks. In addition, the report summarizes the number and type of workers on-site, the equipment being used or which is needed, and the status of material deliveries. Further, the report itemizes any accidents that have occurred, delays and the reasons for them, and any issues impacting the progress or quality of the work. Finally, the report lists all completed quality checks, pending inspections, and any non-conformance issues found. In short, this report helps maintain transparency and ensures that all parties are informed about a project's current state, potential challenges, and future direction.

Work-in-Progress Schedule

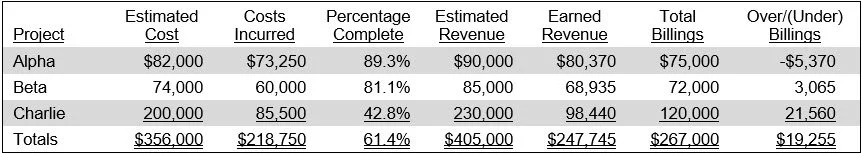

A useful tool for keeping track of the percentage of completion is the work-in-progress schedule. It tracks a project’s ongoing profitability by monitoring three measurements, which are the percentage of completion, amount of revenue earned to date, and the amount of any any over/under billings. The schedule is useful for revealing negative trends early in a project, before they can blow up into larger issues. It also shows the extent to which a project has been either overbilled or underbilled, by calculating the difference between actual billings and recognized revenues.

An example of a work-in-progress schedule appears in the next exhibit, where earned revenue is calculated as the total estimated revenue for a project, multiplied by the percentage complete. This number is compared to total billings to date to arrive at the over/(under) billing for a project.

Construction Accounting vs. Regular Accounting

There are several key differences between construction accounting and regular accounting, which are as follows:

Revenue recognition methods. Construction accounting commonly uses the percentage-of-completion or completed-contract method to recognize revenue, depending on the length and certainty of the project. This allows revenue to be recorded in proportion to work completed or deferred until the contract is finished. In contrast, regular accounting typically uses accrual or cash basis methods, with revenue recognized when earned or received, which is more straightforward.

Job costing vs. departmental costing. Construction accounting emphasizes job costing, where costs are tracked for individual projects, including labor, materials, and subcontractor expenses. Each job is treated as a separate profit center, requiring detailed tracking and reporting. Regular accounting often uses departmental or functional cost tracking, where expenses are categorized by business function rather than by unique projects.

Use of change orders. In construction, change orders are frequent and must be accounted for to update project budgets and revenue forecasts. They can significantly alter project scope, cost estimates, and revenue recognition timelines. In regular accounting, revenues and expenses are usually more stable and predictable, with fewer midstream adjustments.

Retainage accounting. Construction accounting includes retainage, where a portion of the payment is withheld until project completion to ensure quality and compliance. This retained amount affects cash flow and must be separately tracked as a receivable. Regular accounting rarely deals with retainage, as most payments are made in full upon delivery or invoice approval.

Long-term contract considerations. Construction projects often span months or years, requiring ongoing estimation of project status and financial impact. This demands constant monitoring of cost-to-complete metrics and contract asset/liability balances. Regular accounting is usually applied to shorter-term transactions with immediate or periodic financial impact.

Construction Accounting Best Practices

There are several best practices that can be applied to construction accounting, making your accounting system and reports more effective. They are as follows:

Use job costing for project tracking. Implement detailed job costing to assign revenues and expenses to specific projects, allowing accurate tracking of profitability. This helps identify overruns or inefficiencies early in the construction process. It also supports better estimating and bidding for future jobs by analyzing past performance.

Implement percentage-of-completion revenue recognition. Use the percentage-of-completion method to recognize revenue as work progresses, aligning income with project performance. This provides a more accurate financial picture than waiting until project completion. It also helps satisfy lender and bonding company requirements for timely, realistic financial reporting.

Maintain separate bank accounts for large projects. Establish dedicated bank accounts for significant contracts to isolate cash flows and simplify project-specific reporting. This reduces the risk of misallocated funds and improves cash management. It also enhances auditability and accountability, especially when dealing with joint ventures or third-party funding.

Monitor change orders closely. Track change orders meticulously to ensure they are documented, approved, and reflected in contract values and budgets. Uncontrolled changes can erode profit margins and cause billing delays. A formal change order process supports better project control and client communication.

Invest in construction-specific accounting software. Use accounting systems designed for the construction industry, which support job costing, progress billing, retention tracking, and labor management. General accounting software often lacks the features needed for construction’s complex financial structure. Industry-specific tools improve accuracy, compliance, and operational efficiency.